Chapter 1, Part 1 - NA TE HINENGARO

Abstract & Conceptual Designs

PLEASE ENJOY THe WAIATa 'korakorako' BY ARIANA TIKAO WHILe READING CHAPTER 1, Part 1

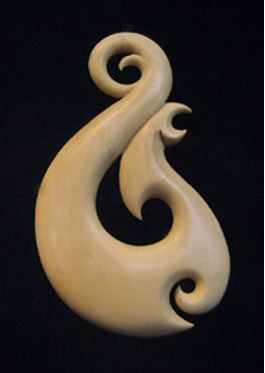

A carving from a sperm whale tooth representing ira, the dual complementary life force

Not long after I began teaching myself to carve bone I read a magazine article which recounted a myth explaining why hei mātau, fish hooks, are still commonly worn as pendants. The story is abbreviated here, but is told in more detail in Toi Whakairo, a book on carving by Sidney Moko Mead. Ruatepūpuke, a grandson of Tangaroa the Sea God, made his own son, Manuruhi, a special hook with the irresistible power of attracting fish, but warned him not to go out fishing alone. However, as his father was busy the impatient son disobeyed, and was delighted to find the hook worked so well that he soon had a great catch. In his eagerness he made two transgressions: his father had not been there to say the proper incantations that would propitiate Tangaroa for using his name for the hook, and he had failed to return his first fish to the sea. Tangaroa punished him by turning him into a tui and taking his likeness for a decoration on his house. When Ruatepūpuke went looking for Manuruhi he found the laden canoe on the beach, but as no footprints led away from it he surmised that his son must be below the waves. He dived after him and found a house decorated with carved figures, some of which even spoke. After setting fire to the house and attacking any of the sea people who escaped, he took his son’s effigy along with some of the silent carvings and returned to his village. Thus the art of carving was brought from Tangaroa to the people. From that time it became a practice to decorate fish hooks to acknowledge the origins of carving. The workmanship and artistry of the carving also served to please Tangaroa in the hope that he might reward it with an abundant catch of fish, which are his children. Special hooks that were more elaborately carved but not functional were sometimes made to please Tangaroa even more. In order to keep a special mātau safe it could be worn as a pendant when not in use. Hooks worn in this way are called hei mātau , and the tradition of wearing them continues to this day.

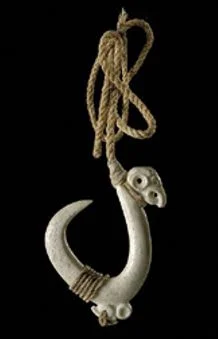

A bone and wood matau with ancestor figures added

As I thought about the concept of pleasing Tangaroa I realised that as a result of the skills learned in making a decorative hook, the quality of functional hooks would also be improved. While discussing this with Te Aue Davis (an expert weaver) of Ngāti Maniapoto, she added that having spent many hours making the special hook, extra care would then be taken to make a strong and durable line in order to keep the treasure safe, and these skills too would be transferred to the working lines.

A whalebone carving that depicts Tangaroa inspecting a matau, or fish hook

This striving for excellence motivated the hook maker to develop other skills, and even perhaps to better heed the advice of his elders, a combination which would ensure a good catch. Those who noticed the fisherman’s regular good catches attributed them to the act of pleasing the spirit world. The rest of the community was thereby inspired to do the same in their own spheres. Collections of traditional artefacts in museums display not only decorative and ceremonial objects, but also everyday items and utensils that are elaborately sculpted and embellished with carving. From my observations I concluded that ‘art therefore became the visual medium which elevated a people from the mundane to an ethic of excellence and provides a model which remains forever relevant.’ Māori had no traditional word for art because it was such an integral part of life: the philosophy of Māori art therefore mirrors their philosophy of life.

A group of matau from Te Papa Tongarewa, showing a diversity of styles with form going beyond function

It is understandable then that even today hei mātau are icons that are regarded as wearable treasures by locals and visitors alike. While they can be seen simply as bringers of good luck, the origins of their power lie in the timeless values of excellence and of acknowledging the spiritual dimensions of life. After reading the mātau myth I decided to research bone fish hooks in museums, and visited the National, Canterbury and Otago museums to study their collections of mātau . I reasoned that after the introduction of metal by Europeans, bone hooks would quickly have become obsolete, and so those collections would be examples of pre-contact carving.

Wood and bone hei matau

Three important observations arose from this study, which remain as guiding principles for my work on mātau . Firstly, the carving of many of these everyday items went beyond the merely functional in order to be aesthetically pleasing. Secondly, the tops of many mātau culminate in a shape that, as well as being a practical projection for securing the line, also represents a stylised head, which is consistent with the important concept that objects are regarded as individuals in their own right. Thirdly, a projection was sometimes left on the outside of the curve, below the point, as an aid for tying on bait. Many of these are face profiles in a range of styles, varying from simple notches depicting forehead, nose, mouth and chin, to recognisable face shapes and also manaia faces.

Two Matau Aka designs

In my own hei mātau designs I have incorporated additonal elements, for example in the two pieces shown above, where the barb shape is a stylisation of the tail of a mako shark. These fish are renowned for their fighting spirit, and this wearable symbol reminds us to continue steadfastly on the paths we choose. I have called the design Mātau Aka because it twists like a climbing vine, and also because traditionally some wooden hook shafts were made from vines which had curved into this shape as they grew. The shafts therefore utilised the strength of the natural form, and a barbed bone point would then be bound to them

Whalebone hei matau from Te Papa Tongarewa

For the hei mātau below I added a figure to the top of the hook to depict the demi-god Māui. I passed the figure on to my friend, stone carver Clem Mellish, who completed the design with a pakohe (argillite) hook. In Māori mythology Māui was so good at fishing that his brothers grew tired of his ways and decided to go fishing without him. However in one version of the story he hid in his brothers’ canoe until they were too far out to sea for them to turn back. Then, using the jawbone of his grandmother as a fish hook, he brought the most massive fish of all to the surface. Māui's fish, Te Ika a Māui, became the North Island, with its eye as Wellington harbour, its heart as Lake Taupō and its tail pointing to the north.

Bone and pakohe hei matau Māui

Whalebone hei matau Māui

Sadly, as Māui went to make peace with Tangaroa for catching this great child of his, Māui's brothers ran around it spearing and cutting it so that its once smooth skin became very undulated and rough in places, creating the mountains, cliffs and valleys that we see today. In the image opposite of a whalebone hei matau Māui, the manaia faces around its rim represent the fish he was famed for catching. The barb is again in the style of a mako tail, as it is Māui who is credited with inventing the idea of a barbed hook.

A whalebone carving based on Māori mythology, with the many corresponding ages of Te Ao and Te Pó shown as manaia faces. It was given to the descendants of Pótautau by Ngā Puna Waihanga, the society of Māori Artists and Writers.